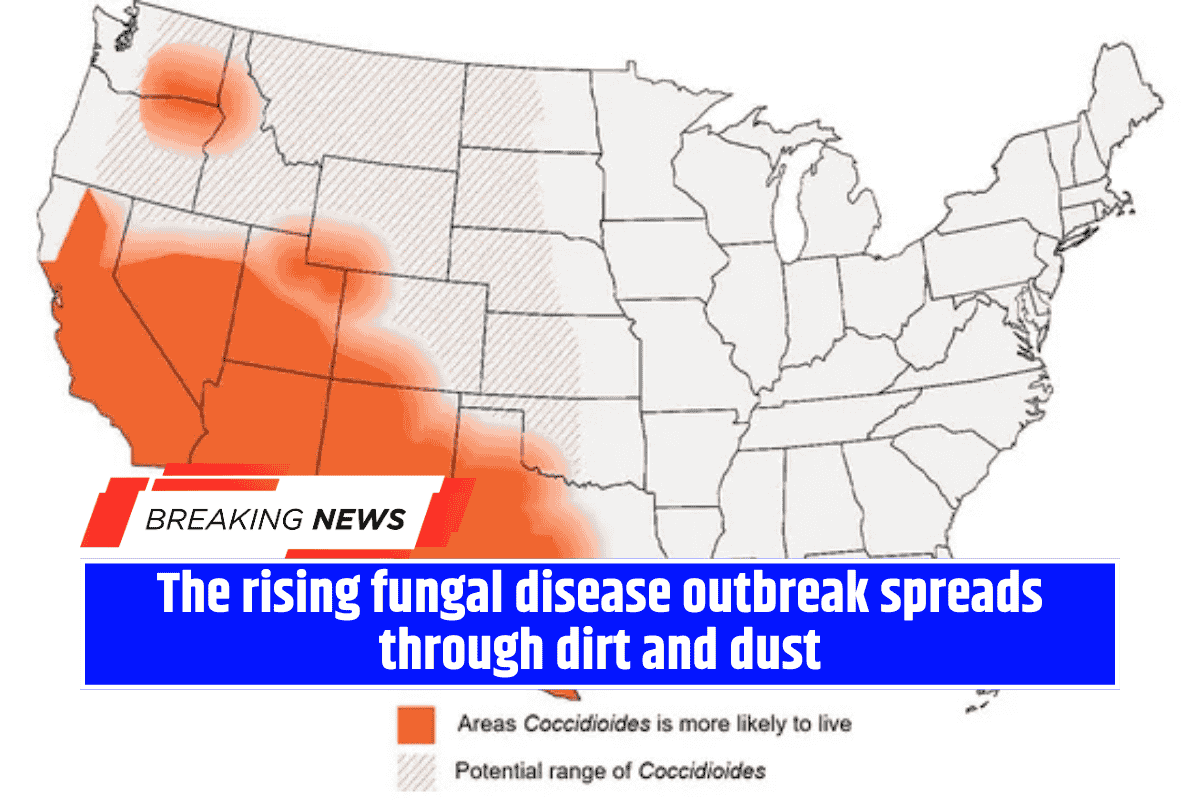

Valley fever, a disease caused by the soil-dwelling fungus Coccidioides, is expanding far beyond its traditional home in the American Southwest.

Once limited to the deserts of Arizona and California’s Central Valley, the fungus is now taking hold in cooler, coastal regions such as California’s Monterey County and has been detected as far north as Washington and Oregon.

Projections suggest that by the end of the century, the fungus could spread into Canada and the Midwest.

Rising Cases in California

California reported a record 12,500 cases in 2024, up dramatically from just 1,000 cases less than 25 years ago. Monterey County’s Salinas Valley — once thought to be protected by its cool, foggy climate — has seen the state’s steepest rise in infections, with cases on track to surpass last year’s record.

Dr. Allen Radner, known locally as the “cocci guru,” says valley fever has become a routine diagnosis: “Two decades ago, I saw one or two cases a month. Now I see three or four a day during peak season.”

How Valley Fever Spreads

The disease spreads when people inhale spores released from disturbed soil. Symptoms often mimic pneumonia or flu and may include:

- Rash

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Fever

- Headache

- Fatigue

While most infections resolve, 5–10% of patients develop long-term lung problems, and about 1% experience severe complications when the infection spreads to the brain, bones, or other organs. Those at greatest risk include people with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, diabetics, and Black and Filipino individuals.

Once infected, people usually gain lifelong immunity. However, no vaccine exists, and diagnosis is often delayed because symptoms overlap with common respiratory illnesses.

Climate Change as a Catalyst

Experts link the fungus’s expansion to climate extremes — heavy rains followed by drought create conditions for spores to thrive. Even a single spore can cause disease. With warming temperatures and prolonged drought, Coccidioides is establishing itself in new ecosystems once considered inhospitable.

Raising Awareness and Advocacy

Public health officials warn that lack of awareness is a major barrier. Many patients receive rounds of ineffective antibiotics before the correct diagnosis is made.

Patient advocates like Dana Bruckner and Bianca Torres in Bakersfield hold educational sessions to encourage people to ask doctors about valley fever.

As Bruckner put it: “It can go undiagnosed. It’s important to advocate for yourself.”

The Human Cost

The dangers of delayed diagnosis are stark. Bill Perske, a 39-year-old butcher from San Luis Obispo County, endured months of unexplained illness before learning valley fever had spread to his brain, causing seizures and hydrocephalus. He now lives with long-term complications and warns others:

“If not, you could just die, straight up. You get written off as a statistic.”

Valley fever’s spread underscores the intersection of climate change, public health, and awareness. As cases climb, health officials stress early recognition, timely treatment with antifungals, and greater education as critical tools to prevent severe outcomes.